Preaching Race and Politics: The Prophetic Fury of George B. Cheever

The abolitionist author of God Against Slavery (1857) remains an inspiration to pastors who refuse a Christianity of silence in the face of oppression.

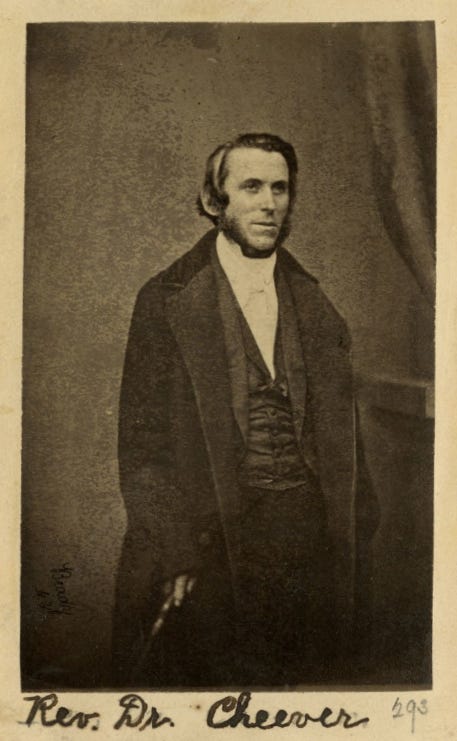

This past week, I found inspiration in the witness of a pastor whose church tried to oust him for his continual preaching on racial justice. In the crucible of antebellum America, the Reverend Dr. George B. Cheever stood as a staunch advocate for racial justice, wielding the power of the pulpit to challenge the conscience of a nation. Many of his contemporaries sought a religion of peace and encouragement, desiring a pastor who provided white Christians refuge in a Christianity divorced from the political realities of the day, but his lifelong commitment to “political preaching,” coupled with his fierce advocacy for the rights of African Americans, rejected the separation of lofty spiritual comforts from tangible earthly realities. His insistence on the freedom of the pulpit to engage with contemporary issues, and his willingness to endure persecution for his beliefs, remains an inspiration and relevant to the religious work of social justice today.

George Barrell Cheever, born in Hallowell, Maine, in 1807, led a Christian life immersed in the moral and political struggles of his time. From his early years, he exhibited an appetite for knowledge, devouring books from his father's bookstore. Graduating from Bowdoin College in the esteemed class of 1825, alongside notable figures like Longfellow and Hawthorne, Cheever pursued theological studies at Andover Seminary. His lineage and his ministry were marked by patriotism, with his grandfather being one of the first casualties in the American Revolution. This spirit of fighting for what is right would become a defining characteristic of Cheever's ministry.

Cheever's commitment to justice manifested early in his career. In 1830, he wrote against Indian Removal, directly confronting the entwined myths of racial inferiority and white supremacy justifying the government’s actions. As pastor of the Allen Street Presbyterian Church in New York in 1839, he continued to write prolifically, publishing works on a range of topics. An imaginative piece on the devastating consequences of alcohol production and consumption, "Inquire at Amos Giles' Distillery," was one of many that sparked outrage and, even though published under a pseudonym, led to his arrest and imprisonment. However, the ordeal only amplified his message and solidified his reputation as a fearless advocate for righteous causes.

The issue of slavery became a festering wound on the nation's soul, dividing families, churches, and political parties. Cheever saw himself as a watchman charged with proclaiming God's truth, regardless of the consequences. He condemned the Fugitive Slave Law, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the Dred Scott Decision, seeing them as egregious violations of God's law and human dignity. His sermons and writings became increasingly focused on exposing the evils of slavery and urging national repentance and emancipation. He also wrote against the oppressive use of “the law” by the already powerful and questioned blind obedience to legislation asserted to follow the Constitution. “The throne of iniquity,” he thundered, “have fellowship with thee, which frameth mischief by a law?”

Key Point: George B. Cheever argued vehemently for the necessity of “political preaching," insisting that silence in the face of moral abomination practiced by the government like slavery was a dereliction of the church’s sacred duty.

He was even invited directly into the halls of the federal government. His high stature is indicated by his audience with President Lincoln just before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. His biographers indicate: “Just before Pres. Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, he received a call from Mr. Cheever accompanied by [fellow abolitionists] William Goodell and Nathan Brown. The president cordially received them, and is said to have welcomed them as ‘prime ministers of the Almighty.’” Their hour long discussion was spent urging the president “to go beyond the promise of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and to abolish slavery on moral grounds rather than as a military necessity.”1

After Emancipation, Cheever saw how white people maneuvered the instruments of government to deny African Americans their full citizenship. Arguing before the House of Representatives and preaching on several occasions to the Senate, Cheever challenged discriminatory legislation and advocated strongly for the rights of Free Black people. As he aged, he remained intellectually engaged, still immersing himself in theological debates of the day.

Moments from Cheever’s Arguments and Sermons

To those who argued that religion and politics should remain separate, Cheever insisted that true Christianity was not a private affair confined within the local church but a transforming force that had to engage with the pressing moral issues of the day. His argument for the necessity of "political preaching" began with the fundamental premise that the Bible had something to say about every aspect of human life, including the political and social structures that governed society. The Bible's teachings on justice, mercy, and love had direct bearing on the laws and policies of the nation. A focus on personal piety failed to address systemic injustices. To remain silent on issues like slavery was to betray the very essence of the gospel message.

The Bible, he argued, clearly and consistently condemned oppression in all its forms and affirmed the inherent dignity of every person, regardless of race or social standing. Cheever was especially focused on racial justice—both Native Americans and African Americans—-with much of his ministry critiquing those who used the Bible to justify racism, accusing them of twisting scripture to serve their own selfish interests. His unwavering condemnation of racism and his insistence on addressing it from the pulpit placed him squarely in the center of the storm.

God Against Slavery (1857)

My introduction to Cheever came by reading God Against Slavery, perhaps Cheever’s most central book. In a sequence of sermons fitting neatly as a series of chapters, he meticulously examined the biblical texts often cited in defense of slavery, demonstrating how such interpretations were based on a flawed approaches to scripture. He repeatedly showed how the Bible consistently condemned oppression and upheld the dignity of all, pointing out numerous laws in the Old Testament that protected the rights of servants, arguing that these laws stood in stark contrast to the chattel slavery of the American South. He also emphasized New Testament teachings on love and equality, insisting that these principles were fundamentally incompatible with the institution of slavery. In short, Cheever confronted the “slaveholder Christianity” of his day, revealing it as a deeply misguided form of biblicism: claiming the strict authority of the Bible to legitimate racial oppression as God sanctioned and God ordained, therefore making it an obligatory Christian conviction.

He not only argued that slavery was wrong, he also confronted the belief among Christians that preaching against slavery was itself wrong. In perhaps my favorite chapter of God Against Slavery, chapter VIII, Cheever systematically addresses the common objections raised against preaching on controversial topics. He confronts the notions among Christians—including his own parishioners—that such preaching disrupts “peace” in the church and hinders spiritual growth. To those who argued that preaching against slavery would disrupt the peace of the churches, Cheever responded with a powerful metaphor, comparing the attempt to silence anti-slavery preaching to the absurdity of stifling warnings about an imminent explosion:

"Suppose a steam-boiler is in such a state of heat and pressure of steam, that the boiler is about bursting. And suppose a party of men on board, engaged in a religious conversation, should run and jump upon the safety-valve, to prevent that noise, declaring that they could not converse while the noise continued. Would that be piety or wisdom? Suppose they asserted that all the danger was from the noise, and not from the racing [i.e. the actual danger of intense build up of pressure]."

He goes on to describe the “noise” from a firetruck—which can be disturbing, but that is no reason to cut it off: “Your fire engine makes a great noise, tearing through the streets to put out a conflagration. Suppose that they should be indicted as a nuisance, while the incendiary goes at large, and the flames prosper.”

Christians require the agitation of “excitement” that truth can bring:

"Ludicrous as it may seem, I have absolutely had the charge brought against my preaching, that it excites the nerves to such a degree that the man could hardly sit still under it. A man complained to a friend who brought him to church one Sabbath evening, that he never was so excited in his life, that he did not come to church to be excited, but quieted, but that he never found himself under such excitement of mind anywhere, and he would not stand it. Poor man, just as if the word of God were nothing but carpenter-work, to make sound sleepers! He did not consider that there are sleepers enough in our churches any day, strong timber, and no danger of disturbing them; and that the very thing we need is excitement by the truth, excitement in the mind, excitement in the heart, excitement in the conscience."

He discusses when churches prioritize a superficial peace over courageous truth-telling:

Between the mealy-mouthedness of preachers, and the mealy-heartedness of the people, with the motto, first peaceable, then pure, there comes to be a most unsubstantial, unreliable state of things. Christians educated in this manner [of seeking peace first than purity] are not to be relied upon for the great battles of principle, the mighty conflicts of the age with evil. There are plenty of men who would fight, if they could only be lashed up to it by some outward pressure and danger; but the habit of seeking first peaceable, then pure, disqualifies them for discerning and battling against the very evils that disturb the peace and destroy the purity.

Cheever preached that true faith manifests itself in action in the struggle for justice and the defense of the oppressed.

The Fire and Hammer of God’s Word (1858)

But wait, there’s more: Other speeches and sermons continue to speak directly to the error of Christians who fail to confront government-sanctioned oppression. In 1858, Cheever gave a speech denouncing slavery, titled “The Fire and Hammer of God's Word Against the Sin of Slavery,” reflective of a tumultuous political climate marked by the Fugitive Slave Act, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the Dred Scott decision. Cheever emphasizes the hopelessness of relying on political or religious groups of his day for the emancipation of slaves due to the perversion of Christian principles by those in positions of authority. Cheever's address focuses on the moral bankruptcy of slavery, particularly criticizing the complicity of the church and its ministers, calling for a revival of true Christianity, and emphasizing the role of the pulpit in awakening the nation's conscience.

Systematic oppression had turned our American moral order upside down. He condemned the nation’s leaders for their hypocrisy and cruelty, stating that they “conceive mischief and bring forth iniquity.” The horrific crime of enslavement had turned into a political virtue. Instead of slavery being renounced as a sin, the act of denunciating slavery was now viewed as the true sin. He observes that even "men of professed piety" use scripture to justify silence, likening their actions to "put[ting] down his [Christ's] light from the candlestick and put[ting] it under a bushel." Cheever places racism in the same category of sin as “lying, perjury, murder, and whoredom.” Our nation is now a “sick and groaning victim” at the mercy of “unprincipled quacks,” subject to the “new experiment of fraud, despotism, bribery, unprincipled and ignorant political surgery.”

Cheever knew racism was about power, and he vividly diagnosed the systems of power of his day by revealing the mechanisms perpetuating racial injustice operating through legal means and financial exploitation. He characterized slavery as a “misery-making machine for the 'agent of all evil’” and likened the systematic dehumanization of slaves to an industrial process where children are “beaten from the birth into marketable articles” and “stamped and sealed them as chattels.” He described a racialized capitalist system that transforms human beings into mere “living spindles, wheels, activities of labor and productiveness.” By “laying our grasp on an unborn race” and declaring that they can only enter the world as “infant slaves, articles of property and merchandise,” future generations were already condemned to misery. American economic exceptionalism was dependent on perpetuating the “sacred native product of domestic manufacture,” namely, enslaved people. As a result, the nation had become a “community of baptized Thugs for the kidnapping of the children of four millions of people.”

He also criticized those who offered token opposition to racial injustice. He witnessed a prevailing attitude of indifference such that white Christians prioritized their own comfort and security. The Church, as “the salt of the earth,” failed in its duty. “If the Church and the ministry, being God’s sentinels to the nation, are bribed or drugged into silence, the nation, by such treachery, will be fatally ruined ere it is aware.” The Church’s true ministry is to serve as “God’s appointed instrumentality for training and awakening the conscience of the people.”

Cheever also knew white Christians were arguing that enslavement followed God’s sovereign plan for the conversion of the enslaved and sarcastically criticized the belief that the forced migration of the enslaved is the “chosen missionary institute of the Lord Almighty,” highlighting the absurdity of this supposedly biblical claim. Again drawing on the scriptures, he draws a stark contrast between a nation committed to slavery and the biblical injunction to remove the yoke of oppression. In the process, he meticulously details how the institution of slavery violates the fundamental principles of Christianity and, because of the sale of people as property and involuntary separation of wives and husbands, makes it impossible for the enslaved to live according to God’s commandments concerning family and marriage.

John Brown and the Failure of the Church (1858, 1859)

Cheever's 1859 sermon, delivered shortly after John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry, stresses the moral imperative to resist ungodly laws. Cheever observes the "practical atheism" of individuals and societies who prioritize self-interest over moral principles, leading to a dangerous prioritizing of human law over divine law. In this sermon, he highlights Brown's sincere Christian faith and his deep sensitivity to injustice. The church's silence and complicity created a vacuum that individuals like Brown attempt to fill. Although at first Cheever seems to promote a type of Christian anarchy, flouting laws based on individual convictions, his argument is more substantive. For Cheever, the actions of John Brown, while misguided, stem from the church's failure to confront the sin of slavery.

Seeing the white supremacist political maneuvers happening aggressively at the federal, state, and local levels, he condemned the idea that a law, regardless of its moral content, demands obedience simply because it is law. Discernment requires that we ask if a law being established at its root results in or furthers an immoral oppression of actual living people. Alongside discussion of the law, he also addressed the orthodoxy of unquestioned allegiance to the U.S. Constitution. Cheever was cautious language treating the Constitution as sacred, contending that allowing the Constitution to be used as a shield for injustice perpetuates sin and compounds it by invoking the law to sanction it.

The logic of following “the law” without critique provides a dangerous justification for tyranny since it allows any group in power to establish and maintain their despotism simply by enshrining their self-serving principles as law.

Cheever closes by warning that if the church continues to remain silent, the nation will face only greater violence and turmoil. He concludes with a plea for Christians to embrace their role as "God’s appointed instrumentality for training and awakening the conscience of the people."

The previous year, in a 1858 sermon titled “The Commission From God,” delivered before the African Missionary Association in Boston, Cheever also saw past “the law” and “the Constitution,” noting that official government policy and legislation could be immoral. Cheever directly confronts arguments of those who claim that injustice is protected by the Constitution and that speaking against it is unwise and divisive. He warns that the church, as the "conscience of the nation," is desensitized to the sin of slavery, leading to a state of moral blindness and vulnerability. He compares the nation to a man whose nervous system is paralyzed, unable to feel the pain of the injuries being inflicted upon it. Unable to confront oppressive power, the Church allows it to make increasingly aggressive demands and erode the foundations of justice and liberty.

Against Indian Removal (1858)

Although his abolitionist messages may be most known, I also read with great interest one of Cheever’s earliest writings, an article published in 1830 titled “The Removal of the Indians.” This marvelous piece consists of a scathing critique of the U.S. government's policy towards Native Americans, especially its push for Indian Removal. Cheever rightfully contends that the justifications offered for Indian Removal—namely the supposed incompatibility of white and Native American cultures and the perceived impossibility of civilizing the “fierce and murderous and imbecile savage” Indians—are fundamentally flawed and morally reprehensible.

Throughout this text, Cheever opposes the “slander,” “sophistry,” and “misinformation” that asserts “a very obvious conclusion that the United States have a perfect right at any time to dispossess a savage community and occupy their soil for the general benefit of society.” Rebuking reasoning that is both “irrational and unchristian,” Cheever urges that it is every person’s “duty to examine facts with an unprejudiced mind, and to give accredited statements their true weight.” His closely argued Appendix constitutes an earnest attempt to do exactly that: carefully debunk and overturn the disinformation of his day.

He condemns the government's attempts to undermine tribal sovereignty by portraying Native Americans as incapable of self-governance and in need of paternalistic oversight. He criticizes the government for citing isolated instances of conflict with certain tribes as justification for imposing sweeping restrictions on all Native Americans, while ignoring the peaceful and cooperative relationships that have existed with many tribes for decades. “He knew that such an attempt, with the admission of what is really true in regard to the state of those tribes, would have been revolting to the moral sense of the whole community; and he therefore artfully here leaves them out of view, and reasons generally upon his description of fierce and murderous and imbecile savages.”

Cheever also dismantles the argument that Indian Removal is necessary for the advancement of civilization and the "designs of nature" by exposing this line of reasoning as a callous disregard for the welfare of Native Americans, who are treated as obstacles to be removed rather than human beings deserving of dignity.

Cheever condemns the government's actions as a betrayal of national morality, finding that the justifications based on expediency and necessity are nothing more than thinly veiled avarice and lust for power. He again targets “the law.” The title page of the printed and tightly compressed text—18 pages of argument, and over 50 pages of a supplementary Appendix—features a quote: “Of all Injustice, that is the greatest, which goes under the name of Law; and of all sorts of Tyranny, the forcing of the letter of the Law against the Equity is the most insupportable."

He also challenges the notion that power equates to right, arguing that such logic was used to justify the Spanish conquest of the Americas and the enslavement of Africans. "They are no other than the maxim that power makes right, and that we may lawfully do evil that good may come." He points out the hypocrisy of this stance, given that the U.S. government has repeatedly entered into treaties with Native American tribes, recognizing their sovereignty and territorial rights. "They are not abstract rights; they are stronger and more evident than any abstract right can be; they are written and acknowledged in almost every treaty, which our government has been called to make with these tribes."

“His mind gives way, like that of multitudes of others, to the false faith that the Indians never can be civilized; and his habits of weighing too often, and too exclusively, the good and the happiness which might accrue to the nation, if these stumbling blocks were out of the way, makes him write of them as if they were neither human, nor endowed with the rights nor the capabilities, which their more fortunate neighbors possess; to be treated, indeed, like so many stubborn animals, and to be sacrificed without scruple, whenever the interests of the whole United States seem to require it. Those who differ from him , and strongly maintain the part of full justice, he treats as men indeed of a misguided enthusiastic benevolence, but with little understanding, and no practical experience in these matters.”

Seeking yet another path to convince people otherwise, Cheever even highlights the embrace of Christianity by certain tribes, particularly the Cherokees, Choctaws, and Chickasaws, and thereby adopting aspects of “civilized” life. As flawed as this argument may be in our eyes today, at the time Cheever sought to convey common ground between Native Americans and the conquering “white Christians” through an appeal to sharing of a common religion.

He also emphasizes their establishment of organized governments, schools, and churches, and their practices of agriculture and trade. He seeks to shame white Christians using a theology they share, saying they lack belief in the redeeming power of Jesus, reminding them that there are “none, however singularly ferocious, whom He cannot reclaim from their savage barbarity.” He cites reports from missionaries, government officials, and the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper to bolster his claims that the progress of these tribes demonstrates the potential for peaceful coexistence and mutual flourishing. “Let us reflect that the first fair trial of the possibility of bringing an Indian tribe into the full perfection of civilization, and under the full influence of the redeeming power of Christianity, is here fast and auspiciously advancing to its completion.”

Cheever concludes with an impassioned plea, calling on individuals to speak out against injustice and urging political action by flooding Congress with petitions and demands for a just resolution to the "Indian question." He believed the public held power: “Let us ask ourselves what each of us can do, to avert the threatening evil, and to add power to the hands of the benevolent. Let each contribute his exertions, and utter his voice, till the united appeal of millions shall swell to such an accumulated energy of remonstrance, as even a despotic government would not dare to resist.” He cites the biblical narrative of Israel's downfall as a cautionary tale, warning that the United States risks a similar fate if it continues down a path of national treachery and moral decay. "Let us listen to the warning voice, which comes to us from the destruction of Israel."

Rights of Full Citizenship for Free Blacks (1864, 1866)

Cheever continued speaking out after the Civil War, his fervent advocacy now directed to newly freed Black people. He consistently emphasized the hypocrisy of a nation that claims to champion liberty while simultaneously enacting laws that perpetuated racial inequality. Here Cheever directly accuses the government of hypocrisy, again challenging both the government and the church to live up to their professed ideals of liberty.

Two sources, published in 1864 and 1866 respectively, demonstrate his direct appeals to the U.S. government, specifically Congress, urging them to uphold the rights of newly freed Black people.

First, “Rights of the Coloured Race to Citizenship and Representation: and the Guilt and Consequences of Legislation Against Them," was delivered before the U.S. House of Representatives on May 29, 1864. This address critiques the government's ongoing discriminatory legislation against Black people, particularly in the areas of military service, territorial rights, and representation in the post-war South. He points to specific examples of unjust legislation, such as laws that discriminate against Black soldiers, denying them citizenship in territories like Montana and excluding them from the benefits of a republican government in the reconstructed South. Cheever also draws attention to the insidious nature of bills that appear to be promoting fairness but actually entrench racial discrimination, warning against the deceptive language used to justify discriminatory practices and urges his audience to recognize the true intent and impact of such legislation.

In his arguments, he also highlights the deeply problematic nature of basing legislation on race. Insightfully, he emphasizes the arbitrary and fluid nature of racial categories:

“[Y]ou have to prove exactly how much of that blood constitutes him of that race, and how much American blood constitutes him of the American race. And to bring these things within the province of law, so as to constitute an indictment for your purpose, you must have and must show a statute providing that descent from the African race constitutes persons of colour, and not only so, but defining how many degrees of blood constitutes the charge of colour, otherwise you cannot convict, cannot exclude from the privileges of freedom, on the ground of colour, persons whom a court room of witnesses would be compelled to pronounce as white as the judges on the bench or the jurors on the jury.”

Second, "Protest Against the Robbery of the Colored Race by the Proposed Amendment of the Constitution," published in 1866, focuses specifically on opposition to a proposed constitutional amendment that would allow States to disenfranchise Black citizens based on their race. The writing consists of a detailed legal and moral argument, exposing the proposed constitutional amendment as a blatant attempt to enshrine white supremacy within the constitutional framework of the nation.

“…for the sake of denying to the negro a participation in human rights. You consent to base the most sacred of your own rights on the whiteness of your skin, in order that you may take away the most sacred rights of the colored race on account of the blackness of theirs. What your fathers fought for unto the death as an inalienable right of freedom, because they were men, you accept as a boon of tyranny, because your skins are white. And this doctrine now taught in Congress makes rebels, slanderers, and hypocrites of your dead fathers, for the sake of rewarding living rebels with power as loyal men, and putting down loyal citizens by disfranchisement under them.”

He describes “States rights” arguments being made immediately after the defeat of the Southern Confederacy as undermining people’s rights as a whole:

“The government are deliberately taking from the people their sovereign rights as people, and putting them out of the citizens' power to recover, and out of the power of the United States to protect, by transferring them over to the States as State rights; not the people's rights, no longer rights at all, but conferred dignities, at the pleasure of the State sovereignties.”

He targets attacks on Black suffrage. Cheever argues that by giving States the power to determine access to the vote, the government abdicates its responsibility to protect the fundamental rights of all citizens and empowers those seeking to solidify established racial hierarchies. Further, he challenges the argument that Congress lacks the authority to intervene in state-level practices. For him, the duty to guarantee a republican form of government inherently includes the power to protect the rights for all citizens:

“It is therefore as perfectly within the province of congressional authority to establish and secure suffrage for the colored race, as for the white, since without this there can be no republican government.”

Calling it a “moral assassination,” he states that once a person “loses the right of representation [they are] in fact considered as caput mortuum, practically a chattel.” Denying voting rights would return Black people to a practical state enslavement.

Freedom of the Pulpit and Expecting Opposition

Behind all of Cheever's argumentation lies the notion of the "free pulpit." Cheever had special confidence in preaching since only the fearless proclamation of God’s word can bring the nation to repentance and ultimately eradicate the sin of slavery. Drawing on examples of Old Testament prophets like Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Amos and from the New Testament, with people like John the Baptist, Stephen, Paul, and John, all of whom faced persecution for their commitment to truth, he challenged his fellow ministers to embrace the prophetic mantle of racial justice, urging ministers to abandon the “policy of silence” and instead “pour out their vials, as God’s commissioned angels,” letting their preaching become as “the thunderings, lightnings, and earthquake shake the heavens and the earth.”

Preachers must be free to speak on political matters because true Christianity was not a private affair confined to the sanctuary but a transformative force that must engage with the pressing moral issues of the day. He insisted that the Bible had something to say about every aspect of human life, including the political and social structures that governed society. To those who argued that religion and politics should occupy separate spheres, Cheever responded with a rebuke: To remain silent on matters like slavery, he argued, was to betray the very heart of the gospel message.

Even with this encouragement, Cheever acknowledged that speaking out against national issues like slavery (noting a fellow minister who told him “it is rather hazardous business”) would inevitably lead to controversy and persecution. However, he maintained that such risks were insignificant compared to the moral imperative to confront evil. Left alone, Christians will use the Bible to support their immoral practices—and not view such preaching as “political” but just “wisdom” and “preaching peace.” From the preface of his book, God Against Slavery:

"But those men who prefer slavery along with freedom, slavery for others and freedom for themselves, and whose plan is to combine both, and give them the same sanction and the same rights everywhere, would be glad to find some support of slavery, some shield for it in God’s word; and, if any one could demonstrate from God’s word that slavery is right, he might do that from the pulpit ad infinitum and they would not regard it at all as political preaching, but as simply the genuine meekness of wisdom preaching peace by Jesus Christ, and the very perfection of gospel conservatism. There are many who, without the least wincing, will hear you preach about the slavery of sin, but not one word will they endure about the sin of slavery."

Cheever's own experiences bore witness to the truth of his words. Throughout his ministry, he faced fierce opposition. He was publicly horsewhipped, sued for libel, paid fines, and imprisoned for his outspokenness. Yet, he remained undeterred. Cheever believed it is the duty of every preacher to preach on racial justice as it is consistent with the teachings of the Bible. The attempt to silence criticism of slavery by labeling it "political preaching" is an attempt to protect themselves from God's judgment. He distinguished between preaching politics in religion (wrong) and preaching religion into politics (according to God's command and essential to saving a nation from perishing in sin). Read the rebuke of the misuse of politics in religion:

It was the preaching of religion in politics, which is God’s own command, both in the Old and New Testament, but the preaching of politics in religion is quite another thing, the work of intriguing politicians and of Satan, seeking to blind the minds of men, and keep God’s light and God’s authority away from their hearts and consciences. If religion be not preached and practiced in the politics of a nation, that nation is on the high road to perdition; for the nation and kingdom that will not serve God shall perish; and if politics be preached and practiced in the religion of a nation, which is the case when religion is not applied to politics, then both church and people perish in their sins.

Cheever may well agree that Christian nationalism fits his characterization politics preached and practiced as the religion of a nation.

He similarly rebuked the "conservatism" that attempts to suppress any mention of topics like slavery in the pulpit. In God Against Slavery, he writes, “The conservatism that would prevent the utterance of God on this subject is a conservatism that stands in the way of righteousness, and yet it makes great pretensions to sobriety and uprightness.” This conservatism values silence over righteous rebuke of cherished sins. He illustrates this point through the story of Jeremiah, who faced opposition when he spoke out against the wickedness of his time, with those in power accusing him of rebellion. Cheever draws other parallels that connect to our contemporary times, highlighting pastors who have been driven from their pulpits simply for speaking out against slavery.

The preacher must act as a "discharging-rod" to release the "concentrated fire of conscience and conviction" in the community. The gospel was not a tool for political expediency or social control but a liberating force. Cheever compares the pulpit to a "park of mighty batteries." This responsibility cannot be shirked due to the potential for agitation.

He was encouraged by a younger generation who resonated with the call to justice: "I have been delighted to find a great enthusiasm among young men, for the freedom of God’s word in dealing with the iniquity of oppression. They feel that it is no necessary part of religion to put down, or conceal, or crucify, our native impulses in behalf of freedom, or our native sense of justice against cruelty and wrong."

Unwavering Advocacy for Racial Justice

Cheever's legacy extends to our own time. His unwavering commitment to racial justice, his insistence on the relevance of faith to public life, and his courageous defense of the free pulpit are relevant for us today. In an era when issues of race and equality remain at the forefront of national debate, and pastoral careers are under threat for consistently advocating racial justice, Cheever reminds us that the struggle for justice among Christians themselves, specifically against comfortable church culture, is never-ending and that leaders of faith have a moral obligation to speak truth to power, even when it is uncomfortable or unpopular.

Like today, Cheever's countercultural stance against slavery drew criticism and opposition. A segment of his own church objected to his support for John Brown and his hospitality towards the radical Church Anti-Slavery Society, which advocated for non-fellowship with slaveholders. This dissent culminated in an attempt to remove him from his pulpit, but that effort was ultimately unsuccessful. Other pastors have not been able to avoid being pushed out of their pulpit for reasons that include disagreement over issues of racial justice. Even progressive churches struggle to actualize racial justice in their progressive congregations.

In the end, Cheever's ministry was characterized by an unyielding commitment to applying biblical truth to social and political issues. He was a preacher, but his prophetic voice extended beyond the pulpit. As a prolific writer, he published numerous articles and pamphlets denouncing slavery and advocating for the rights of African Americans. As an active participant in the abolitionist movement, he worked alongside people like William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. He stands as a testament to the power of faith-driven activism and reminds us that people of faith have a moral obligation to speak truth to power, regardless of the consequences—meaning also that all of us must diligently work to uphold and defend brave preachers when expected opposition occurs, especially when it happens in the back halls and meeting rooms of our own churches.

Want to read George B. Cheever yourself? See a long list of his writings available for download here.

Join me on Bluesky.

For these details on meeting with President Lincoln, see Steve Gowler, “Radical Orthodoxy: William Goodell and the Abolition of American Slavery,” The New England Quarterly 91, no. 4 (2018): 592–624. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26607957.