From Barbara Walters to the White Evangelical Megachurch

Barbara Walters modeled a connection to celebrity culture that links with the style seen in the evangelical megachurches I experienced growing up in Southern California.

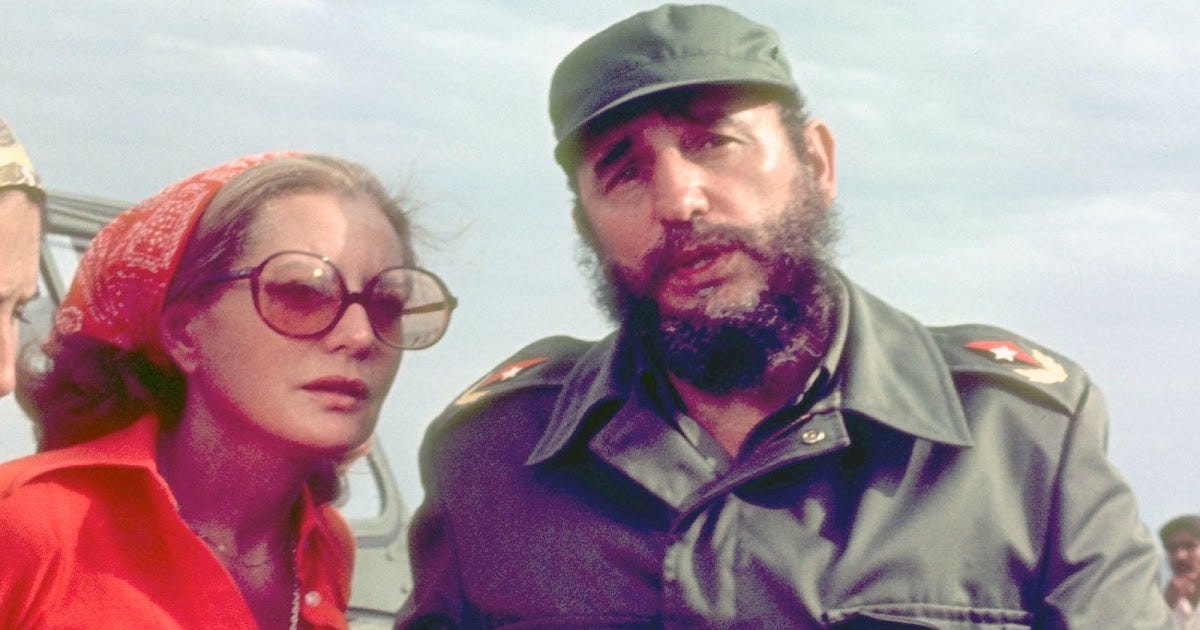

Barbara and Fidel

The news of Barbara Walters’ passing came last night, as the year 2022 is wrapping up. I have many memories of her interviews, but certainly the most vivid is her 1977 interview with Cuba’s Fidel Castro. My parents are refugees from Cuba, left in the early 1960s, and the vitriol against Castro and his regime was as passionate in suburbanizing Orange County as it was in South Floria. Deep, emotional, intense: it was a familiar background to growing up. And of all the interviews Walter’s did, my most vivid memory is this particular interview, that played on the television in my parent’s bedroom, because my dad kept yelling nonstop at the tv throughout the interview, calling him a string of expletives. I barely caught any of her questions, let alone his responses, since my father could not contain himself.

It wasn’t the only interview we watched. My childhood and teen years were filled with Barbara Walters, a journalist who showcased celebrities, bringing their homes into the intimacy of our own homes. I grew up before cable news, with relatively few channels to watch and the start of VCR machines, making “appointment television” key to keeping up with whatever was happening in the world. With little money for any other entertainment, Hollywood, old and new, was always close to me. In Southern California, the local channels are imbued with the sheen of Hollywood glitz — not just movie stars, but sports, politics, quirky talents. If a person was worthy of a news segment or late night appearance, I came to know their names and faces, even if I didn’t usually understand the politics or economics behind their notoriety.

What we seemed to learn from Barbara Walters is what I later learned about charisma from Max Weber.

Barbara Walters exemplified the Hollywood vibe. I understand she was a talented journalist, yet it seemed her celebrity built on the celebrity of others. She centered on markers of status, wealth, and power, yet it seemed key that these people had a distinctive elegance and charm. They were personalities. Her conversations, usually in their own homes, made them more accessible, showing (supposedly) who they were in their everyday life. But they were never normal people. They were special people.

Walters’ focus on their personalities seemed to indicate that their status and wealth came from their special personalities. It’s not that their wealth or their power enables their performativity. Instead, she fostered the impression that the unique charm of their person led to their attaining such great power.

Celebrity culture was my entree to understanding charismatic authority. A lesson that we pick up from Walters, then, is that special people achieve special success. They gain people who admire them and work with them. They get opportunities and funding. They are able to climb a distinctive ladder of success. And they deserve it. They’re special and have a special talent or special mission, so it would be natural that other more ordinary people would give them time, attention, access, support, money, labor — really anything that helps them and makes their lives nicer, easier, more pleasant.

Here’s the kicker: I think that Barbara Walters’ understood that associating yourself with celebrity makes you a celebrity — with access to all its benefits.

Of course, celebrity is powerful. Unpacking celebrity was one motivation for my book Hollywood Faith.

Walters’ celebrity interviews provided a strangely apolitical vision of power. Partisanship was largely ignored. Structural dynamics were not discussed. All this fit very well into suburbanizing Southern California south of Los Angeles. Yes, it was pro-capitalist and anti-communist. In that area, this was simply what it meant to be “American.” Although I grew up with plenty of hippies — often translated into an aesthetic moreso than a political stance — these weren’t San Franciso’s Hyde Park hippies. They were surfer-hippie-pro-development-land-seeking-property-owning-fundraising-marketing-savvy Orange County denizens who loved a beach trip boosted by a growing bank account.

And being able to borrow your way into status was part of the expanding flow of credit so characteristic of 1970s-1990s neoliberal policy agendas. A “red” Orange County really leaned into those economic opportunities despite an overall “blue” California state.

Okay, but why did I mention white evangelical megachurches in the title? Because this morning I was thinking how it seems that all of these dynamics readily flowed into the developing megachurches that grew up around me.

In competition for members, white evangelical megachurches opted for celebrity in pursuit of property and prestige.

Barbara Walters exemplified techniques that were adopted by aspiring megachurch leaders, like Robert H. Schuller, Rick Warren, Church Smith, and others. (Schuller learned from Billy Graham, and Warren learned from Schuller.) Smith’s Calvary Chapel was famous for hosting Contemporary Christian Music artists, building on the concert culture of CCM, which itself built on the energy and prestige of Rock & Roll (think Woodstock), building auditoriums to accommodate this re-worked revivalism for a younger generation. In Southern California, these leaders took on radio and television as soon as they could. Other local church leaders, like Chuck Swindoll and David Hocking, similarly took to the radio. They appealed to Christian celebrities. They brought in more popular, and even “secular” celebrities, to their programs. Yes, the tool of celebrity was used intentionally.

The celebrity of these pastors built on each other. More often than not, they did not compete against each other. They successfully used each other to further echo and reverberate their energies, boosting each other, commending one another in an environment like Orange County where land was still available and the population was still growing.

My take: People like Walters gave these aspiring church leaders the confidence that they did not require wealth or prestige — at first. What they needed was a special personality.

The platform of their churches allowed them to push forward their special talent, special task, special mission. Remember: they picked up the cues that special people achieve special success. If this can be showcased, they could gain people who admire them as spiritual leaders and work with them on spiritual tasks. They will get God-sanctioned opportunities and funding for God-sanctioned projects. And they will deserve it. They and their churches are special and have a special talent for outreach and discipleship and special mission to reach the world, so it would be natural that other more ordinary people would give time, attention, access, support, money, labor as part of their Christian commitment anything that helps them and their church be nicer, bigger, easier, more pleasant.

Now this is a short “hot take” and much more can be said. In no way does “celebrity” alone account for the growth of megachurches. As I’ve written recently, organizational issues are crucial to any functioning megachurch. Yet in understanding where the confidence in celebrity comes from, perhaps Barbara Walters may have fed the imagination of mid-20th Century church leaders far more than we ever imagined.

More on celebrity culture and religion, see Hollywood Faith.

More on megachurch management and the role of celebrity, constituents, and money, see The Glass Church.